You may not have heard of Mr Edward Castronova of the University of Indiana, Bloomington, but he has become a very well-known economist of the virtual world, not so much a student of the games business but more a specialist in the synthetic economies that have grown up around development of virtual worlds like the World of Warcraft (WoW) and Second Life (SL). His October 2006 paper was about real-money trade (RMT) and “economy interaction” which now represent exchanges worth hundreds of millions of dollars.[1] With more and more players prepared to trade goods acquired in the virtual world for real cash and ever more worlds created which encourage such entrepreneurship, Mr Castronova is worried that this crossover will be damaging for the games, in much the same way as the game of Monopoly would be disrupted if houses and hotels were traded for real money. It looks like games are getting serious!

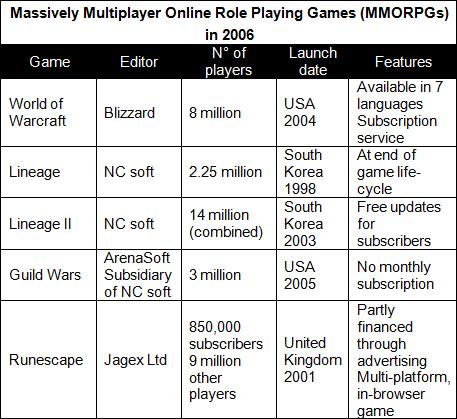

Figures from various sources.

To understand the difficulty of obtaining accurate statistics see Bruce Sterling Woodcock :http://mmogchart.com/

Virtual worlds where players compete on-line in groups are generally called ‘massive, multi-player, on-line, role-playing games’ (MMORPG), and they have become a serious problem in South Korea, not only economically but also in regard to public health. Internet gaming is an enormous enterprise in South Korea. Its RMT economy was estimated at between $830M and $1 billion in 2006, but for a number of reasons this growth has been detrimental to South Korean youth with an estimated 1 million players suffering from symptoms of game addition.[2], [3] The circumstances particular to South Korea have meant that on-line games and gambling account for practically all the game playing market. The games console market is surprisingly small whereas broadband penetration in the concentrated urban areas is at 78 %, which means on-line games like Lineage II and World of Warcraft are exceptionally popular. Young Korean gamers grow attached to their game personas and with no end to the game nor resolution to the conflict, it is difficult for young players to stop. Moreover the club – like atmosphere of belonging to a ‘guild’ of players, working together in these types of games, seems to appeal to young players growing up in a structured society, where Internet use is encouraged and corporate sponsored teams are treated like top sports stars would be, elsewhere in the world. Many thousands of Internet cafés, called locally ‘PC baang’, offer a cheap escape from the pressure of work and school. Here players can stay connected for hours with food and drink available, reminiscent of gamblers at tables in Las Vegas. The downside of this is that, in extreme cases, some players are killing themselves, neglecting to eat properly or take exercise as they play for hours at a time. The South Korean government opened an addiction centre as long ago as 2002, while in April 2006 a game addiction telephone hotline was set up. Hospitals and private clinics have opened units to treat the growing number of addicts.

To make matters worse the proliferation of real money trade only encourages players to play more to support their habit. The South Korean Government proposed legislation in November 2006 attempting to regulate, at least some of the worst excesses of RMT and gambling.[4] It is not clear how far restrictions will go as a result of this legislation but the regulation of such trade is not going to be easy. In the virtual world trading can be done directly with the game provider but also player to player. Game ‘items’ like clothes, tools, weapons and spells that enhance a player’s game-playing capacity can be earned through game play or purchased from a third party. In South Korea two mediator sites, Itemmania and Itembay, dominate the market. Although some virtual worlds like World of Warcraft discourage such exchanges, even there, expert guilds are perfectly able to win items and then auction them off to gain ‘golds’ (the WoW currency), which can then be converted for real money. When organised into virtual game ‘sweatshops, this practise, called ‘gold farming’, produces mass-produced in-game items for sale and is common in virtual worlds like EverQuest, World of Warcraft, Second Life and Lineage. As more inexperienced players join these very elaborate, sophisticated games, so the demand for items grows, encouraging gold farming businesses to spring up in China and South Korea in order to satisfy the demands of less experienced but better-off players in the United States and elsewhere.

Such dealings of course damage and demean the authenticity of the game, but when the items are earned through legitimate game playing they do not necessarily have a detrimental effect on the virtual world economy. Unfortunately however, some techniques to earn items are simply exploiting weaknesses in the game software, making it possible to create virtual currency at will thus creating inflation and instability throughout the virtual world economy. EverQuest particularly has been prone to ‘dupes’, as these exploits are called. On-line games are generally profitable and have a life expectancy far superior to console games. Extensions prolong the experience and maintain interest, but monitoring and policing such games requires more permanent staff and higher running costs. Although game accounts can be blocked and servers taken off-line, success has brought real world concerns as unscrupulous people, with no interest in game playing, exploit the games’ loopholes for profit.

What about virtual worlds without swords and spells?

The popularity of non role-playing virtual worlds also grew dramatically in 2006, and this expansion was accompanied by a number of surprising real world consequences. One of these worlds, Second Life (see article below), has received a great deal of media coverage. Launched in 2003 by Philip Rosedale of Linden Lab, San Francisco, SL, as it is now known, has taken the virtual world by storm. Its particularity is the Linden dollar, a virtual currency which is exchangeable with the US dollar. In the virtual world that runs on Linden Lab’s thousands of servers, ‘unreal estate’ changes hands, and virtual goods are bought and sold through avatars, themselves clothed and equipped with virtually purchased goods.

Whereas some virtual worlds owe their inspiration to heroic fantasy and fiction, SL has more worldly origins – Hernando De Soto’s ‘The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs In The West And Fails Everywhere Else!’[5] Access to ownership, so prized by De Soto, takes pride of place in Second Life. People who produce goods using tools provided by the virtual world ‘own’ their products, which can then be traded with other players for Linden dollars and eventually converted back into real dollars using Second Life’s own currency exchange.[6] Virtual ‘space’ can be purchased outright and nothing prevents businesses from expanding as in the real world. So closely have the real and virtual become, that real world manufacturers have clamoured to set up shop in SL in 2006, notably Nissan and Toyota, as well as Adidas and Reebok. That companies who compete in the real world should continue to do so in the virtual is not surprising, but so have Penguin, Wired magazine, CNET and even Reuters who have their own office complex and virtual correspondent. Second Life is at the moment a little like the Internet say, 10 years ago. Most companies then, did not really understand what it was all about, why they should be obtaining domain names and start having a web presence. Today companies are perhaps more savvy. They see a new medium through which people (i.e. customers) are interacting and, more importantly, spending money, so they wish to be there too. The added value for companies is that SL provides an unbeatable platform from which to launch, promote, test and refine new products, ideas, styles and concepts at a fraction of the cost in real life. For the moment there seems to be a balance between the attraction of a virtual world both to adults and mainstream business interests. It remains to be seen whether this balancing act can be continued by Linden Lab, who run the risk of being too commercial yet are still to make any money from the enterprise.

This emphasis on the business side is, however, to lose sight of the mainstay of any virtual world, that is to say the idea of community. Second Life gives free rein to people’s imagination, liberating them from the constraints of age, social convention and even gravity -allowing them to visit and interact with an enormous on-line community. There is no objective, no points awarded or combat involved. The participants are not even called players but ‘residents’ and it is the user-generated content (UGC) that makes SL so interesting, being far more imaginative and richer than anything Linden Lab would have been able to do alone.

It remains to be seen whether virtual worlds like Second Life can control their economies any better than real life countries, or whether they will experience similar boom and bust cycles. The status of owning virtual goods is also going to be one for the courts before very long. Putting development tools in the hands of the users is very Web 2.0, but it is also taking risks. On-line games in real-time run the danger of being attacked, not only from the outside but also from subversive elements within the games themselves.

[1] Wikipedia provides an overview of this phenomenon. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_economy

[3] See article ‘Hooked on the virtual world: A reality in South Korea’ by Choe Sang-Hun in the International Herald Tribune, June 11th 2006.

[4] “Amendment for Game Industry Promoting Law”

[5] French title: « Le mystère du capital : Pourquoi le capitalisme triomphe en Occident et échoue partout ailleurs », Hernando de Soto, Champs, Flammarion (traduction Michel Le Séac’h). Some people see the literary inspiration for Second Life more in Neal Stephenson’s science fiction novella ‘Snow Crash’, Bantam Books, 1992.

[6] See http://secondlife.com/currency/. For up to date information of exchange rates and for the number of daily transactions, see http://secondlife.com/whatis/economy-market.php