The first phase of the EU Data Retention Directive (2006/24/EC) came into force in September 2007. The legislation was an important development with regard to privacy issues in Europe because, for a number of years, European legislators had been more concerned with protecting the rights of individuals from the worst excesses of open markets, than in the harmonisation of data retention to facilitate cooperation in criminal investigations.[1] The legislation requires, amongst other things, that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and phone companies keep a record of internet usage, e-mail logs, phone call records and location information. Data must be kept for a minimum of six months and a maximum of two years but the directive does not require the ISPs to record the content of messages.[2] Such legislation is supposed to provide authorities, such as the police, with both the data and a sufficient timescale (in which) to continue their investigations. Although telecommunications companies keep detailed records of calls and make them available on a voluntary basis to recognised authorities, because of the particular requirements of the directive, it will not be sufficient for operators to simply tap into their billing records. This is because even unsuccessful calls and prepaid calls must now be logged, together with the location information. According to consultants Analysys Research, ‘The ramifications for the telecoms industry are far-reaching, and will place considerable additional burdens on operators for large-scale data and storage management and security, with no business benefit.’ [3] Similarly many ISPs are not ready for the legislation, meaning that some countries will delay the application of the directive until March 2009.

With regard to the United Kingdom, a bill was passed in July 2007 not only to comply with the European directive but also to define exactly who would have access to the telephone data and what level of access the different agencies would have. To the consternation of civil liberties groups, the new regulations list some 652 public bodies, including local and (district) county councils, who will be able to know who phoned whom, when and from where the call was made! Such detailed information will, from now on, be retained in some of the thousands upon thousands of databases in the UK and elsewhere, that contain Personal Identifying Information (PII); including, but not confined to, individual’s banking details, credit card purchases, travel arrangements, driving license details, tax records, criminal record, family circumstances and medical files. It is estimated that the UK already has over 287,000 data controllers who oversee personal data. For individuals it has become all but impossible to keep track of what is known about them, and by whom! The sheer number of databases and the difficulty of gaining access to them, is putting increasing strain on the level of confidence and trust that is required for a satisfactory balance between a legitimate search for information and the right to privacy. The proportionality of data requests, the integrity of data obtained and held, its correct use, the accountability of the data holder, the consent of the information provider and the rights of access and regress are all key issues that have long been enshrined in Data Protection Acts in Europe and Fair Information Principles (FIPs) in the United States. However, by making private companies, e.g. telecom operators, retain data records for the purposes of public scrutiny, the boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred as to how and when the principles can be enforced. There has also been a surprising lack of public consultation concerning the issues raised.[4] More insidiously, the active involvement of the private sector in gathering and holding information for the state has been likened to a form of corporate ‘conscription’.

Of course, an individual’s right to privacy implies that individuals have some sort of choice and can give informed consent; these principles however will take a back seat when national security is the driving force. Although most people appreciate, and indeed support the need for the retention of data in the context of a suspected terrorist threat or the prosecution of a paedophile ring, there are serious (privacy) objections to the blanket legislation being put into place, as well as unanswered questions concerning the cost of storage and how the data should be analysed and exploited. Such concerns are not new (see “L’Année des TIC 2004”), government ‘snooping’ was an issue throughout 2006 in the United States where it was revealed that the National Security Agency (NSA) was already accessing, as a matter of course, the phone records of at least three US companies in its anti-terrorist activities.[5] The affair intensified during the course of 2007 as AT&T, Verizon, MCI, Sprint and other telephone companies were accused of complicity in the violation of American privacy laws. The ongoing court cases brought by privacy rights activists, protesting against the scale and legality of the interception of communications, have put the incriminated Telecoms companies in an extremely difficult position. As a result, they are now seeking, in a legal, sleight of hand, some sort of retroactive amnesty for their compliance with what they claim were ‘illegal’ requests from the NSA.

The protection, integrity, access and availability of PII data do of course concern us all. What most people do not realise is how personal data is sorted, sifted and then shared between numerous databases, or how little control they have over both the content and the use of their data. We willingly hand over data when asked to, because it facilitates and augments our day-to-day activities, but we concern ourselves little over who oversees the data and what they do with it. Increasingly, we are required to provide personal details, even biometric proof of who we are, as credentials for any number of reasons. The much-criticized US-VISIT procedures, which are part of the agreement between the US and the EU requiring data to be provided before travelling to the US, are a case in point. The EU was uneasy about requiring European citizens to supply such data but eventually acceded to the demands of the State department. According to the BBC, the Department of Homeland Security, ‘mines about 30 separate databases as it checks identities’ [6][7].

In fact, Europe as a whole did not fare too well in the annual report on privacy and surveillance, published by Privacy.org and released in December 2007.[8] Only Greece was classed as having ‘significant protection and safeguards’. Unsurprisingly, the United Kingdom, with its estimated 4.2 million Closed Circuit Television Cameras (CCTV) – or 1 camera for every 12 to 14 people according to some estimates, ranks poorly in the video surveillance table. Taking into account all the criteria measured, France and the UK occupy the bottom two places in the 2007 European league table on privacy protection and citizen surveillance. In France, according to the report, the situation is ‘decaying’ while the UK is the worst performer in both; on a par with Singapore and worse than Thailand.

Data loss and data exploitation

Ironically it was not the retention of data that hit the headlines in 2007 but more often the inability of organisations, particularly governments, to keep hold of the data they had collected. The list on the opposite page catalogues the most important incidents concerning loss of data or breaches in data security. It does not make reassuring reading. Nor does it suggest that even minimum guidelines are being followed. Moreover, while US legislation requires companies to publicise security breaches, not all countries make similar requirements, meaning that many incidents go unreported. Data protection has become a cause for real concern. In the United Kingdom the scale of the data loss has severely compromised government plans to introduce, for the first time, a national identity card which would incorporate biometric data. A serious lack of confidence in the very institutions that are supposed to introduce and manage the identity card scheme will have to be overcome before there is general public acceptance of such a scheme. The public perception is that online crime, data fraud and identity theft are all on the increase, and people are not reassured by the apologies and the advice about how they can protect themselves. It is of course possible to change credit card details, bank and account numbers but it is far more difficult to change one’s address, let alone (children’s) names and (one’s) date of birth. It is estimated that in 2005 more than 8 million Americans were victims of identity theft, although most cases were as a result of the physical loss of wallets, purses and documents rather than data information theft.[9] A survey carried out for UK–based data fraud specialists Garlik, indicated that in 2006 there were 92,000 cases of online identity fraud, 144,500 cases of unauthorised access to computers and 850,000 cases of online sexual offences.[10] It should be pointed out that Garlik is a company offering data protection services to private customers and therefore has a vested interest in publicising online fraud. Nevertheless, any personal identifying information in the wrong hands is a potential invitation to fraud. Savvy fraudsters, armed with your personal information, obtained from a data black market, and along with some of their own biometrics, might be able to ‘prove’ that they are you, more convincingly than you can!

A new vocabulary

The use of different sources of data for surveillance purposes has already generated a new vocabulary, ‘data mining’, ‘data fleecing’ and increasingly ‘dataveillance’ which describes the automated way that information technologies monitor and check the activities of people. In September 2006, The Surveillance Studies Network published a comprehensive report for the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner (the equivalent of the CNIL in the UK) entitled The Surveillance Society. The report highlighted, among many other things, the significant use of data surveillance as a risk management tool, with all the inherent danger of it being used in selective, preventative action. This may be innocuous, like postal codes determining insurance rates; on the other hand, health authorities may employ DNA screening to determine who is likely to respond best to a particular treatment, rather than let individual doctors decide. The report questioned whether governments could, in fact, provide the legislative safeguards to protect their citizens’ liberty and privacy, not because governments do not want to, but because they have put into place systems that they cannot control, understand or even reverse.

Although information collection technologies themselves can be considered neutral, their exploitation is often questionable. The fine line between monitoring and intercepting the telecommunications of suspected law-breakers and doing the same to those engaged in legitimate political protest, is one that is frequently crossed. Nor is the technology, once developed, restricted to its single, initial purpose, and function ‘creep’ will set in. The Advanced Number Plate Recognition network (ANPR), was installed as a military initiative. It is now being used routinely to monitor traffic congestion (charges) as well as criminal activity and fraud[11] [12]. The biggest single development in dataveillance is, however, the cross-referencing of database information and the use of sophisticated software tools that can find connections and relationships between disparate sets of information. Knowledge Discovery in Databases (KDD) is the non-trivial extraction of implicit, previously unknown, and potentially useful information from databases. The mining of information in this way is employed by the F.B.I., by Internet advertising companies, customer relations management, in healthcare; in fact, in any sector where database management is apparent. In the aforementioned (government encouraged) snooping case in the USA, the F.B.I. widened their interest in individual cases by asking telecommunications companies for what is called ‘community of interest’ information; allowing them to analyse interactions one step beyond their initial suspect. According to the New York Times this meant they wanted to know, ‘which people the targets called most frequently, how long they generally talked and at what times of day, sudden fluctuations in activity, geographic regions that were called, and other data.’[13] This is of course exactly the information that the new directive is requiring European operators to store.

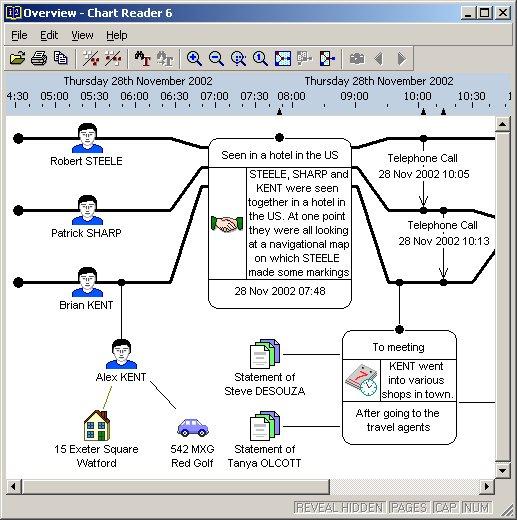

A number of companies have specialised in developing this type of software, notably Unisys, creator of the Holmes 2 system used by UK police forces for major incidents and enquiries, and Analysts Notebook from the ChoicePoint company, who specialises in effective link and timeline analysis. (See screen capture)

Marketing companies can employ transactional data gathered from their customer base and compare it with data from external, publicly available, institutional or specialist data collection agencies, in order to allow target groups to be profiled or areas for advertising or promotion to be identified. In France, La Poste offers marketing solutions to companies who wish to tap into their customer database, which contains masses of data about the addresses it delivers to, and when available, who lives there. [14]

Behavioural Targeting

The data trails left by Internet users interest online advertisers in particular, who seek to target potential customers by obtaining as much information as they can about where the user has been, for how long and why. Google, already masters of the sponsored link, took over their chief rival in internet advertising, the lords of the Web page banner, Doubleclick, in April 2007. The merger, approved by the Federal Trade Commission in December, is still being considered by the European Commission at the time of writing, but the issue of the traceability and the identifying nature of IP addresses is an increasingly controversial one.[15] The wholesale information gathering conducted by groups like Yahoo, Microsoft and Google, using Web analytics and data algorithms for marketing purposes, is coming increasingly into question. The FTC published some guidelines at the end of 2007 in order to encourage self regulation in the sector. [16] In the guidelines the FTC clearly pronounced in favour of consumer consent in the data collection and stated that, “Companies should only collect sensitive data for behavioral advertising if they obtain affirmative, express consent from the consumer to receive such advertising.” On the other hand, it was unable or unwilling to state what the FTC considered ‘sensitive data’ to be; instead they asked for help from interested parties in an attempt to define it. Not an easy task; for example, someone who performs a Web search for ‘wedding cake’ may be perfectly happy for that information to trigger recipes from a commercial Website offering professional catering services. However, if the search request concerns cancer treatment, abortion clinics or sexually transmitted diseases, it may be that the user would prefer more discretion. The ‘clickwrap’ agreements that most data harvesters use to make users ‘opt-in’, do not, for the moment, discriminate between search requests and their sensitivity. More ominous is the consolidation within the sector, as characterised by the Google / Doubleclick merger. In behavioural targeting it is the sifting and sorting of the mass of data collected, as the user moves from one site to another, that is going to make all the difference between a hit and miss approach, and targeted advertising. Companies with a large range of sites and services that can collate such data will inevitably attract more announcers. Moreover, collecting useful data is easy and effective. The simple technique of ‘Web bugging’ or ‘pixel tagging’, i.e. placing a one pixel square, blank .gif image on an ordinary Web page yields the following information:

– The IP address of the computer that fetched the tag,

– The URL of the page that the tag is on,

– The URL of the tagged image,

– The time the tag was fetched,

– The type of navigator that fetched the tagged image,

– A previously established cookie value (if one was present).

The above information, when analysed and compared with data already held, will, as one advertising mantra goes, ‘put the dog food ad in front of a dog owner’.

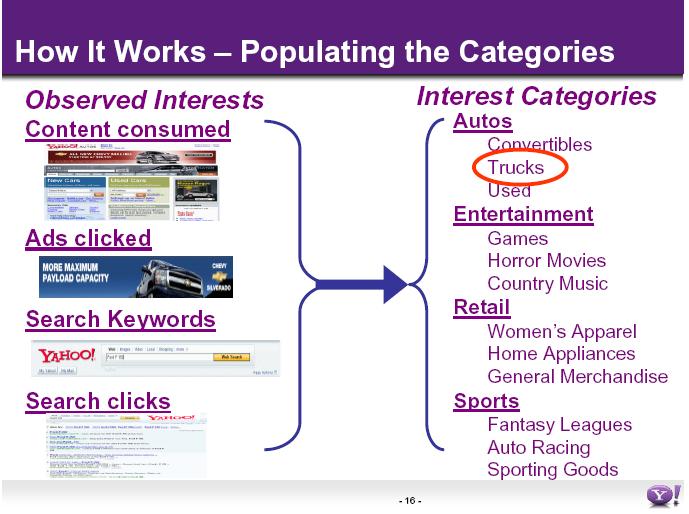

Advertisers like Yahoo and Google argued before the FTC that advertising does no harm and that targeted advertising was to everyone’s benefit, as well as providing free Web services. Yahoo’s submission outlines clearly its strategy and scope. (See slide capture)

Yahoo follows its users from Yahoo property to Yahoo property, harvesting data, analysing it, meshing with global advertising network Blue Lithium, (acquired by Yahoo with much less fuss in October 2007) [17] and using its advertising brokerage, Right Media Exchange, to ‘greatly improve (users’) online experience’. [18] Such an argument however belies the increased customer knowledge base that these non-traditional media giants possess. The traditional market forces that long operated between announcers, pollsters, market researchers, advertising groups and the press, TV and radio, have been effectively short-circuited by the emergence of groups like Google and Yahoo. Equally, these new giants are becoming the arbiters of what can or cannot be advertised in this way. Searches on Google with the keywords ‘bereavement’ or ‘anorexia’ will not generate adverts. This is not the case for ‘hair loss’ or ‘haemorrhoids’.[19]

Phorm and Facebook

The possibility of ISPs allowing third parties to data mine their customers’ connections, to better target advertising, is not a comforting one in the opinion of many privacy rights observers, for whom it is akin to banks selling customer account details or a telephone company furnishing connection details for commercial purposes. Phorm, a company specialising in such advertising, has tried, not unsuccessfully, to sign-up major ISPs in the UK to an ‘anonymous’ Web tracing system which tracks all Web activity from an IP address.[20] Phorm (rather naively) raised a storm of criticism by proposing a technologically sophisticated system that promises both targeted ads, while guaranteeing customer privacy. In an edifying video clip promoting their product, (since withdrawn), Phorm drew attention to the tactics of other, less scrupulous advertisers before proposing their own, ethical approach to spying on Internet users’ habits.[21] Phorm’s elaborate, compartmentalised and probably well-intentioned strategy seems to have backfired in that it has served only to raise the general awareness of the sensitivity of PII and highlighted the increasingly ambivalent position of ISPs, which are under pressure to generate other revenue streams in order to compensate rights owners’ loss of earnings through illegal downloads. In such circumstances, any method that would allow them to profit from their bandwidth largesse is tempting.

Maximising revenue was also the aim of the major Web 2.0 social networking sites like MySpace, Beebo and Facebook.  The popularity of these sites continued to grow during the course of the year, set against a background of agitated commercial manoeuvring. Whereas the personal identifying information associated with an IP address seems somehow sacrosanct, the PII associated with a MySpace blog or a Facebook member is on general view and can be exploited by anyone, including the site owners, regardless of the wishes of the member. Yes, there are warnings and yes, there are privacy policies, but when one sees the amount of freely volunteered information available, it is no wonder that a whole group of specialised Web sites have grown up to collate and exploit the data. Commercial interests often ride roughshod over other considerations.

The popularity of these sites continued to grow during the course of the year, set against a background of agitated commercial manoeuvring. Whereas the personal identifying information associated with an IP address seems somehow sacrosanct, the PII associated with a MySpace blog or a Facebook member is on general view and can be exploited by anyone, including the site owners, regardless of the wishes of the member. Yes, there are warnings and yes, there are privacy policies, but when one sees the amount of freely volunteered information available, it is no wonder that a whole group of specialised Web sites have grown up to collate and exploit the data. Commercial interests often ride roughshod over other considerations.

In their eagerness to exploit the potential commercial power of endorsement, Facebook introduced a system called Beacon in November 2007. If one had a Facebook account and purchased anything from one of the many Web partners of Facebook, the purchase data would then be added to the Facebook profile page of the owner, thus informing all his or her friends.[22] This was accomplished by the one pixel gif Web tag system outlined above. Beacon was initially opt out, that is to say the users had to specify that they did not want the information to be shared. As a result of pressure from a great many users who did not want their holiday plans, birthday present purchases or video rental titles ‘shared’, Facebook’s owners eventually changed Beacon to an opt-in system. Whether the data is still being collected from those who have chosen not to opt-in is unclear. At the same time as Beacon was launched, another marketing tool, ‘social ads’, was presented about which Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO boasted, “you will be able to select exactly the audience you want to reach, and we will only show your ads to them. We know exactly what gender someone is, what activities they are interested in, their location, country, city or town, interests.” [23]

Ownership and management of social data are issues at the forefront of the debate on data management, but for the vast majority of users of communication and information technologies, the opt-in opt-out option is one that is no longer offered. Modern life co-opts users’ personal data and life patterns willy-nilly, from simple phone call information to geo-location tagging, from near-field payment systems to RFID tags, from surveillance cameras to face recognition, from fingerprint log-ons to DNA proof of parentage, from the cradle to the grave our digital selves will be examined by data agents with differing agendas. It is going to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for individuals to retain any meaningful control over, or obtain any redress with regard to their digital selves.

_________________________________________________________________________

Data theft, security breaches and data loss highlights 2007[24]

* February: U.S. Dept. of Veteran’s Affairs, Virginia USA, Medical Center lost data containing medical details about 535,000 military service veterans and the billing information of 1.3 million doctors.

* February: a 28-month audit of weapons and laptop control by the F.B.I., revealed 317 computers lost, missing or stolen. In many cases it was impossible to determine whether the equipment missing or stolen contained sensitive information.

* March : Dai-Nippon Printing Co. Ltd revealed that 8.6 million items of personal information, including names, addresses, telephone numbers, insurance certificate numbers and credit card numbers, had been stolen by a computer operator working for a subcontractor who then sold the data to Japanese criminal organizations, mail order, and direct marketing businesses.

* April: some 200 petrol stations in the UK were involved in a credit card and debit card scam, which skimmed millions of pounds from motorists’ bank accounts; money which was then used, according to some sources, to finance the Tamil Tigers’ armed struggle against the Sri Lankan government.

* July: Computer hackers targeted the American-based, cut-price fashion retailer TK Maxx over an 18 month period and stole purchase information from 45.7m credit and debit cards in the US and the UK. The firm, which announced the hack in January, revealed that US transaction data included customers’ driver’s license numbers, Military ID numbers or Social Security numbers.

* July: Fidelity National Information Services, a US financial services company, revealed that a database administrator working for a subsidiary had stolen and sold bank and credit card data on up to 2.3 million customers.

* August: Monster.com, the employment specialist site, made public that details on 1.6 million job seekers had been stolen.

* September: US brokerage firm Ameritrade found malicious programming on its servers similar to that discovered on Monster.com, allowing spammers to steal names, addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses from some 6.3 million customers.

* December: HM Revenue & Customs had a catalogues of data losses in 2007, the most important being the loss of two CDs containing the personal details of all families in the UK with a child under 16, (some 25 million people) who were present on the child benefits database. Details included dates of birth, addresses, bank accounts and national insurance numbers. Earlier in the year it also lost a laptop containing customer details of the well-known investment companies Standard Life, Liontrust and Credit Suisse Asset Management, when it was stolen from the boot of a customs’ officer’s car, as well as disks containing telephone conversations.

* December: details on 3,000,000 candidates for the UK driving theory test were lost in Idaho, USA. Data went missing in May 2007.

* January 2008: UK’s Ministry of Defence announced that 69 laptops and seven personal computers were lost in 2007. Some of these contained unencrypted data, including passport, National Insurance and driver’s licence numbers, family details, and NHS numbers for about 153,000 people who had applied to join the armed forces, together with banking details of around 3,700 people.

_________________________________________________________________________

[1] For a scholarly but succinct review of the legislation see Francesca Bignami, Privacy and Law Enforcement in the European Union: The Data Retention Directive, in the Chicago Journal of International Law Vol 8 N°1 (233-254), 2007.

[2] Governments may delay its application to Internet access, Internet email and Internet telephony until February 2009. Countries may, if they wish, go further than the proposed EC legislation, as Denmark has done.

[4] For an interesting examination of trust and confidence in this context from a French perspective, see the article by Annie Blandin, ‘Protection des données personnelles et confiance’ in La société de la connaissance à l’ère de la vie numérique, GET 10 ans, juin 2007.

[5] For the legal background to these events, see the article by Claudine Guerrier in this edition (in French).

[6] See ‘Do you know what they know about you ?’ at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/7107975.stm

[7] Border officials are also vigilant concerning US citizens. Anybody suspect can have their phone or laptop confiscated indefinitely for examination.

[8] Leading surveillance societies in the EU and the World, 2007, http://www.privacyinternational.org/

[9] Federal Trade Commission survey published November 2007 available here http://www.ftc.gov/os/2007/11/SynovateFinalReportIDTheft2006.pdf

[10]https://www.garlik.com/press/Garlik_UK_Cybercrime_Report.pdf . One of Garlik’s directors is none other than Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

[11] The CNIL and the UK Information Commissioner differ in their appreciation of ANPR. The French public body considers that people have the right to travel anonymously on French roads whereas the nominative nature of ANPR being linked a limited number of potential drivers of any one vehicle is not seen as intrusive by the British.

[12] In an effort to reduce ANPR fraud Germany introduced a special license plate font called FE-Mittelschrift, with the FE meaning it is Fälschungs-Erschwert, i.e. difficult to forge. See http://www.kottke.org/07/11/femittelschrift

[13] See FBI Data Mining Reached Beyond Initial Targets here http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/09/washington/09fbi.html ?em&ex=1189483200&en=48ef7b2758c89e78&ei=5087 %0A

[14] See http://www.laposte.fr/solutionsdata/site/index.php#/prospection/ for a complete list of its commercial services.

[15] An illuminating voyage into one’s own Web searching is possible for all those with Google accounts through Web History, https://www.google.com/accounts/ManageAccount which lists all the searches conducted through Google from the beginning, Web searches, images, sponsored links used Blogs visited, etc.

[17] Having already purchased a 20 % stake in the company the year before.

[18] Full pdf available here http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/ehavioral/presentations/2mwalrath.pdf

[19] Google has recently had problems with advertising which accompanied a subject search for ‘abortion’.

[20] BT is apparently going to adopt Phorm technology.

[21] Phorm knows these very well because in a former life Phorm was known as 123media Inc, an adware company.

[22] For an overview of advertising and online media concentration see Steve Anderson’s article http://coanews.org/article/2007/our-Web-not-theirs. Partners in Beacon include Ebay, Blockbuster Travalocity and Sony Pictures.

[23] Widely quoted, from Tech Crunch http://www.techcrunch.com/page/205/ ?22,38,17,25,07,2007

[24] For a full list of US data losses see http://www.privacyrights.org/ar/ChronDataBreaches.htm